Interview with Christopher Kirubi

Block 336, 22 July 2020

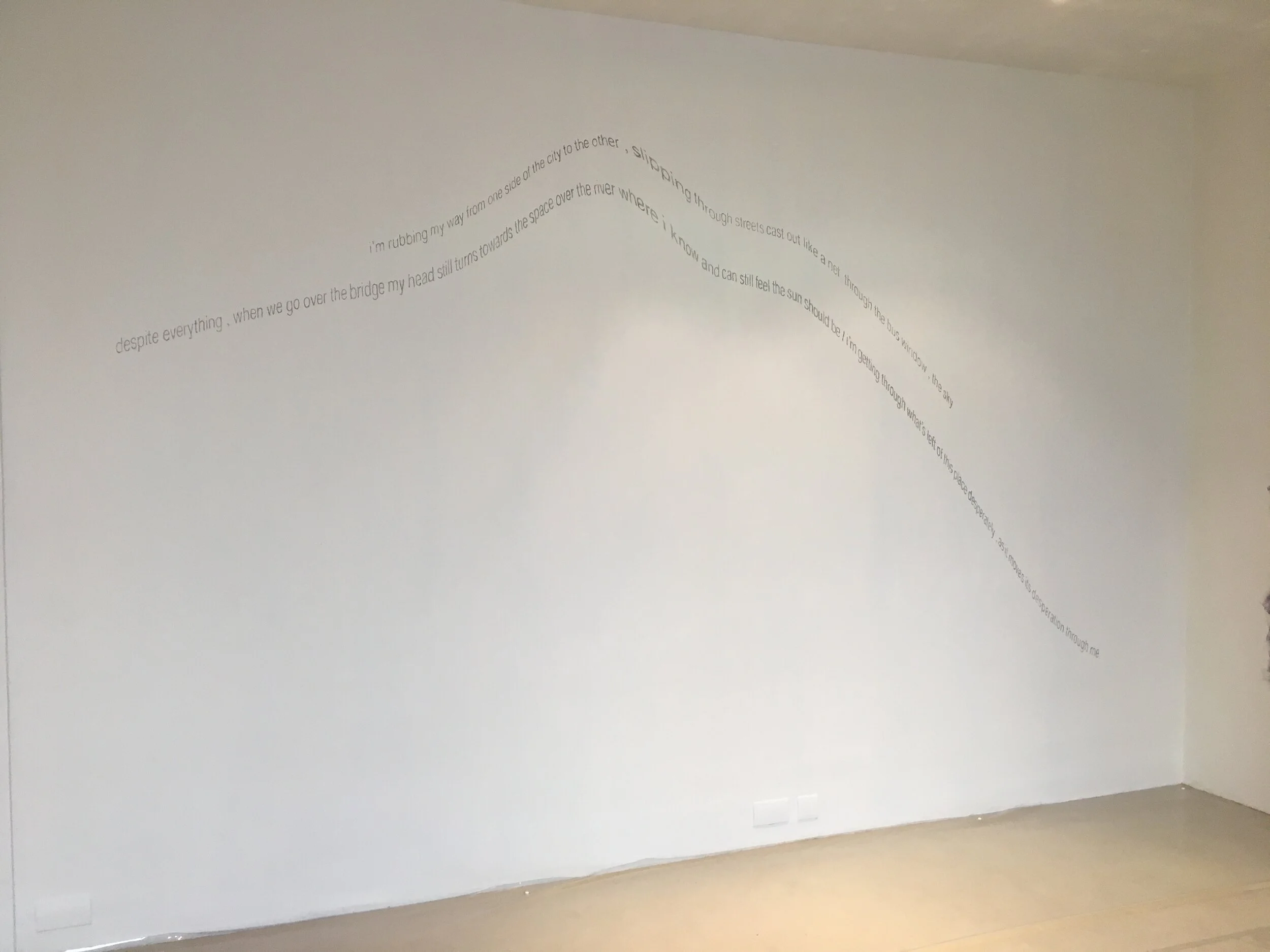

Christopher Kirubi, the world through me, 2018, graphite on wall

Christopher Kirubi graduated from the Slade School of Fine Art in 2018 and has been featured in numerous exhibitions, events and performances both nationally and internationally, including CAMPUS Fugitive: The Unexpected Beautiful Phrase (2019) at Nottingham Contemporary, Breathless (2018) at 198 Contemporary Arts and Learning in London and Young Black Romantics (2018) at Lafayette Anticipations in Paris. Christopher is also a member of BBZ BLK BK, an online directory of queer womxn, trans and non-binary artists of Black ancestry. Christopher is the third recipient of Block 336’s Studio Residency Award, a free three month studio residency.

In your practice, you describe how you draw on the ‘mutability of images, objects and text to negotiate the limits of sexuality, gender, race and desire.’ It seems as though you are harnessing the slipperiness of disciplines and materiality as an expression of the fluidity of sexuality, gender, race and desire; approaching both your practice and these subjects as boundary-less, mutating forms. How does this manifest in your process?

Words like mutability hold an important place in my process because, rather than nullifying boundaries, they allow me to hold space for changing states, like the phases of the moon. I don’t believe that things like race or sexuality, or even artistic disciplines, are without boundaries at all, but that they contain internal contradictions that can pull and push at where their boundaries lie, and where they appear in conversation or in conflict with one another. I try to act in my process in the same way as I try to act in my friendships and communities; I try to be responsive, open and self-aware of my position.

Negotiation denotes a process of conversation in which multiple positions and perspectives are drawn together in order to do business. I think that, since the time of writing that statement, I have become much more influenced by relationships of care and of playfulness - ways of being and working together that are led by the heart. So many different threads of my practice have emerged over the years that I find it really hard to understand how to talk about process, but I will always feel committed to holding space for myself and whoever and whatever I’m working with as something mutable, complex and nuanced - in a way, I think this commitment is the process.

Poetry is arguably one of the most direct art forms, due to the immediacy of its translation from the internal idea to the external form. I am thinking particularly of your text ‘talk, music’, commissioned for The Range at Eastside Projects last year which seems akin to a stream of consciousness. Can you tell me about your writing process and how your poetry emerges?

Writing, for me, has always been about the testing out of dimension. I know that poetry is sound and so at some point a sonic, or oral dimension must be explored, but also poetry can be the turning of a page and so the way the sounds settle onto paper must also become part of the experiment. When I’m working on a piece I enjoy bouncing it around different mediums, writing it out by hand, then typing it on my phone or computer, imagining I’m reading it aloud to people and then playing the recording back to myself. The piece starts to gather and shed parts of itself until at some point it starts to reject my input. When I get really stuck, I often employ the strategy of writing a letter to the piece, explaining to it how I feel about it and where I feel we might be missing or misunderstanding each other and what I’d like it to become.

‘talk, music’ was a really interesting piece to write because I was in the middle of the experiences I was writing about. I would spend all day hanging out with all the artists in the show, helping to install the exhibition and logging and holding memories and conversations in my head and then would sit at my desk in the evenings and try to shape them into something readable, without having much time to reflect. In the end, the piece became something gestural which I think reflected the process.

You are part of BBZ BLK BK, an online directory of queer womxn, trans and nonbinary artists of Black ancestry. How important is collective exchange and collaboration to your practice?

It is extremely important. I find the world to be sometimes extremely hostile and, if I feel I am alone, my tendency is to withdraw and to lose sight of any knowledge that worlds exist in which my reality and my experiences can be seen and recognised. There are so many collectives, some of which are named and some of which have no name, to which I owe the knowledge that my future is something worthy of imagination and love, and that the sense of formlessness which often surrounds queer black people does not contain any inherent truths or bear any relationship to our visibility to the white, heteronormative, classist, patriarchal ableist world, but indicates our unbounded sense of emergence. I think that making art with other people who have a stake in the unfolding of these black queer worlds is incredibly powerful and necessary and makes the world more possible for me to live in.

You choose to engage with the conditions under which your work is seen. Can you tell me more about this and how the viewing of the work impacts the work itself? Do you see the interaction between the work and the viewer as a form of productive exchange?

I occupy a contradictory position here. As queer and trans black people it is difficult to feel that our work as visual artists working with painting, sculpture, and installation, is taken seriously; we are not offered physical exhibition opportunities with the same readiness that many white artists are. Instead, we often find ourselves constituting the public programming, publications orbiting exhibitions, screenings and performances. While I would love for a more equitable distribution of these kinds of institutional platforms, I am also very aware that occupying these kinds of exhibiting environments is not always safe for us and the reasons for this are complex. In part it has to do with the people who hold the resources to distribute these kinds of spaces and the kinds of interactions we have with them. I feel that it also has to do with the structure of exhibiting itself; the kinds of gazes at play; the recourse to the white cube as a default in many instances; and the way a relationship to art which prioritises consumption and circulation is encouraged, which often removes works from any understanding of their history and context. On top of this, the idea of exhibiting is fraught with a tension transposed directly from the feeling of being in my body in public as a black transfeminine person. Unfortunately I tend to burden my art with these anxieties I have about being seen in public, and with my desires for safety and love. My work so far has struggled with the idea that it must be seen in order to be, but I feel that I am approaching a turning point with this now and am seeking more strategies to explore this exchange.

What impact do you hope that your residency at Block 336 will have on your practice?

I hope to fully embody the myth of the artist lost in the vacuum of the studio setting, which is kind of a joke but also not, and in doing so be able to create work in a way I did not think was possible before. I hope that it gives me the space to untangle some of the anxieties and worries that I have around making work, and that I also can reconnect with the joy and fun and intuition of process-based ways of working. I feel like I’ve had to skirt around the truth of my practice for a long time and so I hope to take a few steps closer towards the heart of what I want to be as an artist.