Interview with Jennifer Martin

Block 336, 25 August 2020

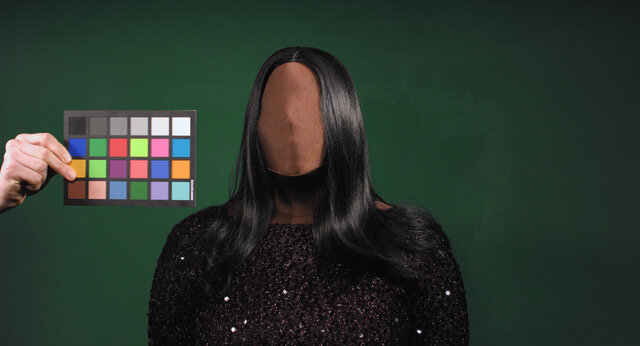

Jennifer Martin, Meanwhile On Set…’ (still), 2018, digital video, duration: 15 mins. Image courtesy of the artist.

Jennifer Martin graduated from her MA at the Royal College of Art in 2018, where she now works as a Visiting Lecturer. Her work has been featured in numerous festivals and screenings, including at the 36th Kassel Dokfest (Kassel, Germany, 2019); the B3 Biennial of the Moving Image (Frankfurt, Germany, 2019); and Inner/Outer 2, A—Z (Art Licks Weekend, London, 2018). Solo exhibitions include TEETH at Primary & b.Dewitt Gallery (Nottingham, 2019), and Channel 6 at Turf Projects (London, 2019). Martin works as an Associate Lecturer at London College of Communication and is Co-Director of not/nowhere, an artist workers’ cooperative run by Black artists and artists of colour, focusing on analogue film, audio and digital practices.

Your work 'queries the psychological and social construction of race and citizenship'. Could you expand on this and the thematic underpinnings of your work?

A lot of my previous work deals with race and citizenship, but I would say this phrasing has shifted for me in the last two years or so. With projects like Meanwhile on Set… the moving image work centres on British black and black bi-/multi-racial actresses, with attention to conditions of acting that impress on that intersectionality. The women are the only ones to appear fully on-screen. The white male co-stars that would typically dominate focus are fragmented and disappeared. They appear as hands, and shoulders, truncated, hanging in the wings. Their words - quips, monologues, diatribes, and turns of phrase - are magnified. At the same time, this device of keeping the men anonymous works to evade the satisfaction (for white viewers) of pinning the racism to individuals and individuals only and instead aims to speak to the systemic. This is perhaps best enacted in the 'Talk Show' segment when the unseen audience laughs along to the host's racist jokes and boos when Gabby Moore, played by Rochelle Rose, rails back. Equally, when laughter arises in viewers of Meanwhile, the systemic isn't restricted to the screen.

In your film TEETH (2019) you explore the violence of the UK immigration system through the narrative of a couple being interrogated by two Home Office agents about their spousal visa application. The film becomes increasingly surreal and performative as the interrogation goes on, culminating in the couple dancing for the agents. I was struck by the way in which the film sheds light on the idea of privacy as a privilege; the violence and power exerted in the systematic denial of people's privacy; and the humiliation undergone by those applying for visas. Can you talk a little about the formal techniques you use to explore these subjects? For example, I am thinking about the way the camera crops in on Charlotte and Myles' (the couple applying for visas) mouths as they are made to read aloud a series of intimate text messages they've exchanged.

The communication evidence was a central part of the film. It is a requirement for UK Spousal Visas and a total invasion of privacy that you have to willingly participate in for the process. The split screen separates their experience as the 'united front' they attempt to present and introduces the characters of Charlotte and Myles to us individually. It also evokes the separation experienced during times in their relationship, which is referenced in the messages they read aloud. The close-ups and extreme close-ups on the two are reflective of the intimacy of the text. Moreover, the shots depict the level of inspection and this fixation around mouths. For me, surrealism must stretch from reality, it has to retain a tether. The communication evidence is wholly real, but its recitation strives to convey the emotional reality of the experience.

In TEETH, the music is an imperative part of the work's tension. The music stops and starts, underlining the contrast between the stress and the mundane bureaucracy of the visa application process. How important is sound and music to your work generally?

Sound and music are fundamental to my work. With sound, I consider what to position subjectively or objectively; how close we come as a viewer to a subject or a source of a sound. I consider sounds that might stretch or appear to come from the other side of the screen. The speakers in the installation of TEETH at Primary were all positioned as a ring around the rugs. Viewers sitting in front of the screen were entrapped by the audio. Sounds in TEETH such as the bodily noises from Charlotte and Myles build to become elements of the score. Music has always been a love of mine. I grew up with my father's collection of vinyl records and insistence on assembling the best quality sound system. Music draws something intangible and yet so bodily in listeners.

For your exhibition Channel 6 at Turf Projects in 2019, you collaborated with 3D illustrator Tadeo Soriano to create an anthropomorphic immigration van that formed one of the show's key characters. How important is collaboration to your work?

The collaboration with Tadeo Soriano was such an essential element of the Channel 6 exhibition. The character Tadeo created captured the sinisterly cute aesthetic of the immigration van. My moving image practice is particularly collaborative, and it is one of the things that draws me to the medium. In working with performers, together we unpack the character, language, and context through improvisation. Those sessions are usually short rehearsals, but they give breath to the script. I was lucky to have a mentoring session with actor/director-screenwriter Beru Tessema on directing actors, and one of the things that stuck the most from his advice was to create an environment in which an actor could discover and respond rather than interpret.

Much of your work explores immigration and assimilation and interrogates the government's hostile attitude towards immigrants. In Channel 6, for example, the moving image contrasts sites of power (such as the media's portrayal of the Royal Family) with sites of resistance where bystanders 'by collective compassion and force' challenge Immigration Enforcement. Do you view your work itself as a site of resistance against unfair power structures?

In the last two years, the body of work was focusing on immigration and assimilatory processes – Britain Been Rotten, Channel 6, and TEETH. Nonetheless, I don't believe that art can be the singular saviour of subjects. I do hope for my work to operate as a disruption, an agitation. I centre black characters in my work, embedding traces of absurdity and dark humour in their lived impositions, but never endeavour to educate or make an audience understand the experiences of a character, as though it is something to be transmitted through the screen and appropriated or used to assuage. Instead, I hope that these traces are intuited for the viewers that they have meaning for.

Mouths and teeth appear frequently in your work, particularly in TEETH and Britain Been Rotten (2019). We see this in the title of TEETH, referencing Amber Rudd's 2017 statement in a letter to Theresa May that 'illegal and would-be illegal migrants and the public... need to know that our immigration system has "teeth"'. One of the Home Office agents in the work also wears a contraption that pulls his lips apart, revealing his lips and gums. We also see a poster displayed in what appears to be the staffroom, stating 'Employees must wash their mouths before returning to work'. Britain Been Rotten references the Middle Eastern and Asian mythology of the 'tooth worm' to explore the violent narrative of the immigrant/migrant as rot on the British system. Could you expand on the symbolism of mouths and teeth in your work?

With the body of work referenced, the starting point was Amber Rudd's letter that was leaked at the height of reporting on the Windrush Scandal in Spring 2018. Still, in following the thread of the subject, this tied into a long historical legacy of rot and control. The Wellcome Collection exhibition Teeth (2018) provided scope for in-depth study of the history of teeth in the UK, and encounter with the ephemera part and parcel of that history. The publication The Smile Stealers (2017) by Richard Barnet, which inspired the Wellcome Collection exhibition, was an additionally formative source of historical background. Teeth in the British Empire were tarnished by the violence of enslaved production. The plantations' abundance was circulated as bounty to the masses, crossing economic stratospheres. Transatlantic slavery is as ingrained as the grit of British enamel, individually lifting British citizens as well as nationally cementing the power of the empire. Teeth are entangled with a sense of nation and nationality.

Your work is interested in the instability of bodies and their slippages. Has the COVID-19 pandemic affected or augmented your way of thinking in relation to the bodies you portray?

I found it difficult initially to continue working on the film I am currently writing and developing. I was writing about this instability and thinking about bodies that might peel, or melt, or crumble, as well as researching CGI influencers and characters and trying to imagine the appeal of the digital fantasy. One of the things that helped me to not be afraid of this proximity to the pandemic was an e-flux podcast interview with artist Anicka Yi. She posed that the coronavirus both divides and unites and has reminded us of the lack of true individualism; we can no longer think of ourselves as independent entities. The virus expands notions of instability and conflicts with our understanding of what a human body is, a human body we have come to learn is also a thing that leaks. Naturally, my notions of the instability of bodies take new meaning in the contextual threat of coronavirus. I'm exploring this without directly focusing on COVID-19 or using it as a plot device.