Interview with Tom Worsfold

Block 336, 8 June 2020

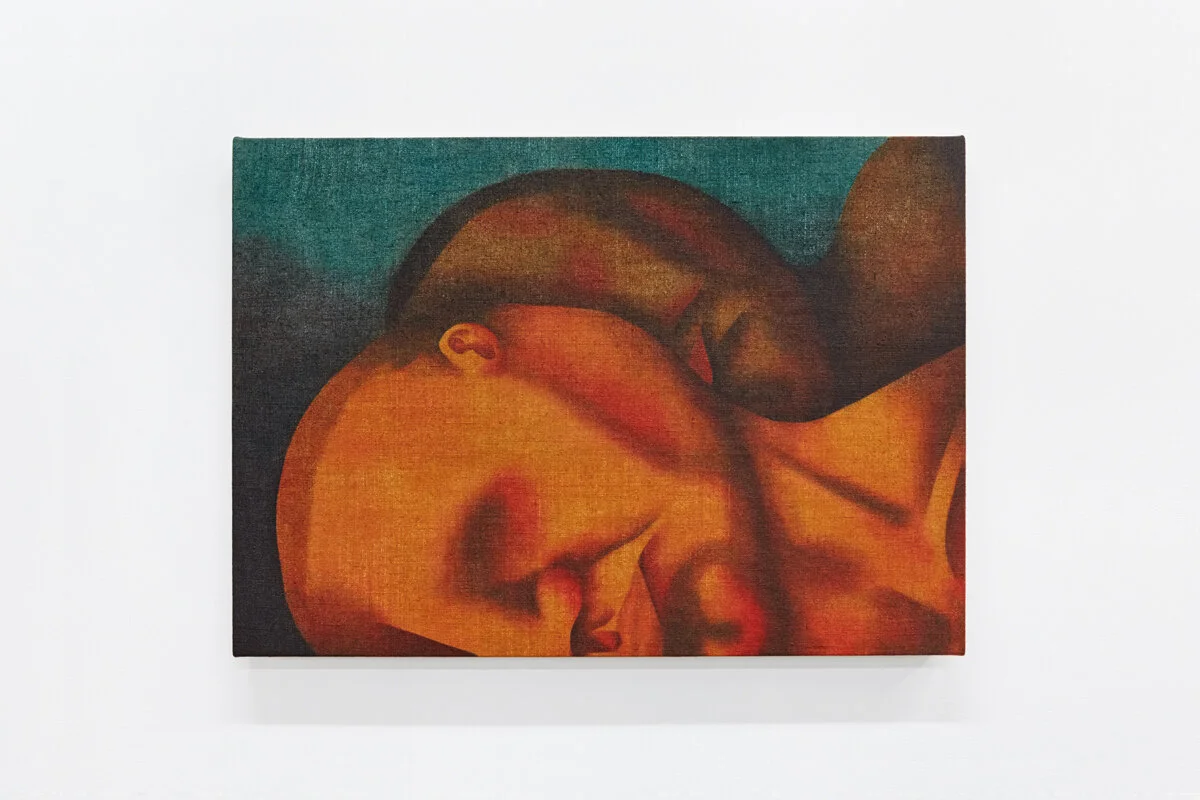

Tom Worsfold, Fallen, 2020, Acrylic on flax, 60 x 84cm

Tom Worsfold is an artist and Fine Art tutor, currently based in London. He studied at the Royal Academy Schools and the Slade School of Fine Art and has exhibited widely across the UK and internationally, including: Castor Projects, Carlos/Ishikawa, Recent Activity, Mackintosh Lane, Assembly House, Space K, Spike Island and more.

Your new body of work for your postponed exhibition The Sleepers, at Block 336, demonstrates a shift in materiality; from painting on canvas to painting on flax. How did that shift in your practice come about and has it altered your approach to your subject matter?

The work in this show emerged after a long period of reflection. Older paintings were made on smooth canvas to allow a specific set of graphic effects and techniques. I got to a point where I knew the logic of these paintings too well – I could predict their outcomes before starting. I began questioning whether certain formats were inhibiting both my creativity and subject matter. So I set about finding a new painting ground, testing pretty much all of the coarser family of fabrics: linen, hessian, scrim etc. Flax felt instantly magical because of its colour, irregularity and ruggedness. I was drawn to the problems it posed for the watery washes and layered effects in previous paintings. This led me back to basics: colour mixing, testing mediums, stitching fabrics etc. In this sense, the time taught me to listen more to materials in the construction of a painting and to remember the joy in playing with materials. The new surface felt like a stranger with its own personality. Initially, painting faces was a method of giving personality to the flax… getting to know it. In the past, my subject matter felt easier to summarise. I think material practices have the power to redefine our understanding of what we think we do. Yes, the body is still there, and yes, the autobiographical beat is present, but I think they interrogate something more experiential – both in their making and viewing.

Your new work is much simpler, compositionally, than some of your previous work (I’m thinking about the series of paintings you showed in your exhibition ‘Models’ at Castor Projects in 2018-2019), interspersing bodies and objects. How do your compositions materialise, in terms of your process? Why have you moved away from the inclusion of objects in your new paintings?

I think about those works like Giorgio De Chirico’s ‘metaphysical’ paintings, where body parts and everyday objects are mixed together like lines in a poem. The resulting mood is a hybrid of associations and readings triggered by the symbolic language. I am attracted to paintings which construct a sense of ambiguity. I see this as a technology for dwelling with ideas that escape verbalisation. I am still thinking about the way painting can articulate internal states, experiences or moods, but with more directness. There is something confrontational about a face. Painting a head which is more or less life-size is a strangely reflective experience. It felt liberating to work without the pressure of using objects to code experiences and instead occupy a more simplified form.

In terms of process, I still don’t plan the paintings. I tend to avoid drawing or composing beforehand because it kills the fun. More recently, I’ve concluded this process is an integral part of the subject matter. Working straight onto canvas, flat on the floor, distorts and approximates imagery, but also allows unexpected things to happen. Working with fast-drying liquid glazes means I need to make quick decisions in the way the faces are constructed. A kind of cartooning or caricature… the overall expression shifting as each facial feature is glazed and built up. The resulting imagery is always slightly uncanny to me. I am engaged in a constant process of having to ‘make good’ unplanned shapes or disappointing colour choices, an assimilative process which informs my relationship with these beings (or selves).

There is a profound intimacy to your new paintings. Looking at them feels like the witnessing of private exchanges, either between two people or a person and themselves - the watching of someone at a moment when they don’t know they are being looked at. How do you imagine the viewer’s position within and alongside these works? I am particularly interested in the paintings as a commentary on and subversion of the ‘gaze’, whether that gaze be male, voyeuristic or otherwise.

That description feels about right. I see them now as private exchanges with oneself, and in the paintings with multiple figures these can be seen as versions of the self too. To me, the eyes and mouths feel static – they are posing, waiting, thinking, sleeping… The title of the show came from this observation: Sleepers in the literal sense but also as a metaphorical state.

I am interested in what you suggest about the gaze. This was not something I consciously considered when I was making the paintings but, writing now, I think there might be some overlaps with psychoanalytical ideas such as Lacan’s ‘mirror stage’. Moments of self-recognition or mis-identification happen constantly throughout our lives. Especially in an artistic practice, where one can develop material proxies of the self. Each painting uses awkward, badly-lit iPhone selfies, which I took to capture specific angles or anatomical features. In the process of painting, these fragments became strange, buried and distorted. Although the paintings could be described as self-portraits, I’m not really interested in saying anything about myself. They just use me to get to somewhere else. They perform a kind of inwardness. To evoke an intensity or awkwardness in one’s own presence – something more universal.

Also, I think a lot about the various stereotypes of beauty within our culture – for example, how the male body is represented both in heteronormative media and queer cultures. How do these representations become engaged or assimilated by the psyche? A friend recently gave me a copy of Byung-Chul Han’s Psychopolitics, which has been at the back of my mind. The author discusses the relationship between neoliberal power and the way individuals act upon themselves. He talks about sexiness and fitness being productive, disciplinary categories of selfoptimization. In terms of a painting practice, I feel there is a link between these ideas and the way we utilise materials. I am fascinated by the way everyday acts and relationships with objects become private languages. What is the relationship between glazing a canvas and applying foundation? Painting thus becomes a test bed to re-enact and abstract these questions.

The bodies in your paintings are usually fragmented, distorted. In this new body of work, I’ve noticed a particular emphasis on mouths, closed (I’m thinking of ‘Monument’, ‘Angel’ and ‘Fallen’). What significance does this have? Is it connected to the mouth as orifice, as our leaky method of communication, sealed up in this case, in relation to the idea of the body and the canvas as interfaces?

I think mouths are so wonderful to paint. The tiniest alteration can change the attitude entirely. A single brushstroke can turn ‘passionate’ into ‘pissed off’. Fragmentation and distortion are still present in the paintings but in a quieter way. When I began these paintings, I became fascinated with images of the Mona Lisa. I had always overlooked the artwork because of its renown, but there is something magical about it: the sfumato blurs, the horizon, the asymmetrical face… The blur makes the mouth expression uncertain, precarious, or between states. I was thinking about mis-recognition as a kind of technology. The way paintings of faces produce a kind of delay in perception. But also, the holding of multiple ideas simultaneously within one field – something I have also tried to do in previous work.

This series began by trying to capture a pout (Monument) and in doing so, it took me somewhere else. The act of painting reveals unexpected qualities in one’s subject. And sometimes it also attributes unexpected qualities to the subject. I’m always compelled by the way figurative language produces this kind of residue or supplement whenever it is used to represent reality. It’s this rare substance which one cannot plan for and cannot adequately describe – it belongs to the experiential technology of the painting. Your question also reminds me of Deleuze’s writing about Francis Bacon and his paintings’ facial features e.g. the scream. Deleuze describes the body escaping through a scream or the way a face can dismantle around a smile. The pout began as a lighthearted way to think about body language, facial gestures and the unspoken codes we use. The heads feel sealed off – eyes closed and mouths silent. To me, this makes them more like objects and further in tune with the object-hood of the painting. Open eyes and mouths have an animated quality I associate with cartooning. To maintain the optical surface fizz, I wanted to reduce any movement within the symbolic faces themselves.

Your paintings have previously been based on everyday life and daily observations. Has the daily life of this ‘new normal’ of lockdown, the COVID-19 pandemic, seeped into your visual language?

The most immediate thing that comes to mind is the increased screen time. Not just social media, but communicating over video software like Zoom and FaceTime. With the above in mind – thinking about facial recognition and communication – the screen has a kind of uncanny to it too. The delays, buffering, pixellation, out-of-sync facial expressions… I have noticed the increased need to visibly emote onscreen whilst speaking. There are no subtleties on Zoom, everything needs to be more expressive or said clearer. There is an emphasis on clarity. I’ve read many articles recently about the fatigue caused by the change in body language on these platforms. It has made me reflect on my painting practice but also appreciate ways of being with people, such as the power of sitting with somebody in silence. Or looks between friends which signal in-jokes instantly. Or coded, knowing glances across a bar. There is something very human about these quiet forms of experience and awareness, which I am appreciating is also part of the technology of art. All of this has also made me long to see art in the flesh again… to experience volume, dimension, saturation, texture, granularity. With this in mind, when I get back the studio, materiality is something I want to continue exploring.